Raptors

In North Yorkshire in the nineteen fifties, thanks to intensive gamekeeping, large raptors were as rare as hen’s teeth. Travelling back to the UK in recent years was, for me, like entering a different world.

In the mid-sixties, the skies in The Gambia, even over Bathurst (now Banjul), were full of vultures, with a richer variety of large raptors in the immediate hinterland. I regularly saw more than twenty species in a day on the Central Plateau of Turkey, although the volume of passage in autumn was minute compared to the Bosphorus.

Indian White-backed Vultures were so numerous over Lahore in the early seventies it was difficult to spot other soarers! In Ethiopia I could watch Lammergeiers and various hawks and eagles from my veranda. The littoral in Mozambique, on the other hand, was relatively impoverished, but my discovery of wintering Sooty Falcons there more than compensated.

It was surprising how many raptors found their way to the Azores in mid-Atlantic, where Common Buzzard is the only resident. (Açores actually means ‘hawks’ in Portuguese.) In the Algarve, some birds find their way to Cape St. Vincent in autumn, with most returning east to cross to Africa at the Strait of Gibraltar. Many of these pass over my house, in both directions!

The most impressive of the vultures has to be Lammergeier, with its colourful plumage, aerodynamic contours and unique, bone-breaking habits. I saw my first in central Turkey in 1967 and my last in Kazakhstan in 2015 but the image below was taken near Dessie in Ethiopia, where villagers dumped rubbish, including bones, into a ravine. Lammergeiers are widespread throughout the Ethiopian highlands and I regularly saw them over Addis Ababa.

In Ethiopia, Rüppell’s Vulture was common in the rift valley, where it was out-muscled at carcases by Lappet-faced.

I did not expect to see Rüppell’s in Portugal but, in recent years, a few have arrived in Iberia with Griffons which had wintered in Africa. Large flocks of Griffons congregate near Cape St. Vincent in late autumn (below left) and I have twice seen juveniles with them. Black Vulture numbers are increasing in southern Iberia and odd ones also occur with Griffons in autumn in the south-west.

None of my Fish Eagle slides from Africa have survived and I failed to photograph Bald Eagles in Canada or White-bellied Sea-Eagles in Sri Lanka. I first encountered White-tailed Eagles in northern Greece in 1964 and then in Turkey in the late sixties, when the species was still relatively widespread. Their successful reintroduction into Britain has somewhat degraded their iconic status, but it was still good to see native birds in Lapland in 2012. This bird was one of several in the Varanger Fjord, apparently not enjoying one of the worst springs in recent memory.

The majestic Aquila eagles never fail to impress with their size, power and aerial prowess. Sadly, none of my Imperial Eagle images in Turkey have survived (Agfa film deteriorated much quicker than other brands!) but I have seen Spanish Imperials from my house in autumn and managed to capture one immature being seen off by the local Kestrels.

Most of my Steppe Eagles have been in Africa, but this immature (below left) was hunting soft-furred field rats in the Cholistan Desert in Pakistan. The adult was in the Ethiopian rift valley.

The resident Tawny Eagles in Africa are smaller and paler. This pair had just killed a Cape Rook.

I saw Golden Eagles regularly in Sutherland but never managed to photograph one. They are much rarer in the Algarve, but this immature paid me a visit in April 2023.

The moniker ‘eagle’ has been used too freely in my opinion when the more generalistic ‘hawk’ would be more appropriate. Harrier-Eagles, Hawk-Eagles, Long-crested Eagle and the buzzard-sized Booted Eagle all fall into this category.

In The Gambia, Long-crested Eagle was always associated with Borassus palms. In Ethiopia, telegraph poles seemed to do just as well.

I now see Short-toed Eagle almost daily in the Algarve. There is a breeding pair about 1km from my house and overwintering birds are becoming more regular. Global warming is also encouraging them to spread north, but I was still amazed to hear Dean MacAskill had recently seen one in my old stomping ground of East Sutherland, where I spent almost twenty years from 1990! The bird (below left), photographed from my Algarve veranda, is in ‘typical’ adult plumage but paler, white-headed individuals are not infrequent.

The nearest Bonelli’s Eagles to my Algarve base are a little further away but I see adults from my house occasionally (often very high up) and wandering immatures can appear at any time. Strangely, locally bred birds are mostly pale-phase. A more reliable site is in Alentejo province, east of Castro Verde, famous for its Great Bustards and Black-bellied Sandgrouse. This adult was near the settlement of Entradas in April, in close company with an adult Levaillant’s (Atlas) Buzzard in breeding habitat. The pale-phase juvenile was photographed from my veranda.

Despite my opening nomenclatural homily, Bonelli’s is more like a ‘true’ eagle and almost as worthy of ‘Aquila’ status as the kite-sized Wahlberg’s Eagle in East Africa. When I arrived in Addis Ababa in June 1975, I found a pair with young in eucalypts in the large British Embassy compound. Incredibly, it was the first breeding record for Ethiopia. Raptor ‘legend’ Leslie Brown came up specially from Nairobi, half-expecting them to be Tawny Eagles. As we arrived at the site, one of the adults left the nest calling ‘kip – kip’. “Expletive deleted . . . . you’re right, I’d know that call anywhere!”

At the risk of pedantry, the term ‘kite’ is another nomenclatural mish-mash, being applied to a wide range of very different families. How can the angelic Black-shouldered and Swallow-tailed forms be closely allied with much larger scavengers and multiple other unrelated genera in Central and Southern America?

Let’s stick, then, with the ‘true’ kites as we Europeans know them. I am familiar with three forms of the ubiquitous Black Kite: the migratory nominate Eurasian, the more resident African race and the black-eared form in the Sub-Continent and the east. The nominate race is occurring regularly in Britain now (I even saw several in Sutherland) but the adult which arrived on Santa Maria in June 2010, and stayed for over a year, was the first for the Azores. In Portugal, it does not breed in the Algarve but I see plenty of migrants in autumn. The spectacle of seeing large raptors on the move is hard to beat and I have chosen the image which best conveys this experience.

In my publication ‘Taxonomic Teasers’ (2022) I addressed the complex issue of the Old World red-tailed buzzards. I had long felt the ‘lumping’ of Long-legged with the smaller cirtensis form in North Africa (which does not have a melanistic phase) was a nonsense and am relieved the split has finally been made. However, the adopted English name of ‘Atlas Buzzard’ is hardly appropriate for a species extending right across North Africa and into Jordan, so my alternative of ‘Levaillant’s Buzzard’ would be better.

Migration watchers on the Rock of Gibraltar had been seeing puzzling individuals with a combination of buteo and cirtensis features for some years, which became known as ‘Gibraltar Buzzards’. Clearly, hybridisation was taking place in North Africa and the genes were also becoming evident in the Spanish buzzard population. I even saw a ‘Gibraltar-type’ buzzard on Santa Maria, but it did not stay long enough to pollute the resident island race.

A few Long-legged Buzzards, close in size to Bonelli’s Eagle, do reach western Iberia in autumn. When I was studying the birdlife of Kefallinia, Long-legged Buzzards arrived in March and bred there. Further east, in Crete, Long-legged seems to be only a winter visitor. This partially leucistic individual was photographed in eastern Crete.

In the Algarve, I began to see increasing numbers of ‘pure’ juvenile cirtensis Buzzards in autumn, then adults at other times of the year, suggesting colonisation of Iberia had already occurred. The adult pictured (below left) was in breeding habitat in Alentejo Province in April. Most of the autumn juveniles are ghostly pale (below right).

Another overdue ‘split’ is Steppe Buzzard: the small, highly migratory vulpinus. The melanistic male Ron Johns and I saw in a pass in the Taurus Mountains in southern Turkey in early May was hardly larger than the Hooded Crow circling with it. There is some intergradation with Common Buzzard in south-east Europe (Vaurie,1965) and the small individual I photographed from my Algarve veranda in the autumn of 2024 (arriving on the same day as a Long-legged Buzzard) shows features suggesting it may have originated from this area.

In the sub-tropics, Red-shouldered Hawk was common in Florida and Dark Chanting Goshawk equally abundant in The Gambia and Ethiopia.

Since seeing my first juvenile Montagu’s Harrier hunting over Cowpen Marsh, Teesmouth in August 1955, it has remained one of my favourite birds. During my spring migration watch from the southern tip of the Ionian Island of Kefallinia in 1994, I particularly enjoyed the spectacle of dozens of harriers (Marsh, Hen and Montagu’s) arriving over the sea from Zakynthos in late April, clearly using the chain of Ionian islands as stepping stones after the longest crossing of the Mediterranean from Tunisia. In eastern Crete in the spring of 2005, a good proportion of the migrants were Pallid. Some Pallids take a more westerly route back from their African wintering grounds and the female (below right) was feeding with eight Montagu’s near Entradas in late April 2022

The female Montagu’s which passed my house in Brora in late April 1997 was the first record for mainland Sutherland. In October 2002 I was summoned to inspect a road-killed ‘Hen Harrier’ at Invershin which had a French ring. To my surprise it was a juvenile Montagu’s which, it transpired, had been rescued from a damaged nest in south-east France and released from care. It’s appearance in Sutherland’s ‘north-west fault’ suggests it may have been the bird seen in Iceland earlier that autumn.

I see a few Montagu’s Harriers from my house in the Algarve in autumn and there was a stunning melanistic bird near the Cape in September 2017. In Portugal, they breed on the plains of Alentejo in good numbers. In early April 2017 eight, accompanied by a female Pallid Harrier (see above), were hunting together over a stretch of newly-cut meadow, right beside the Entradas road, offering a wonderful photo opportunity.

With no resident falcons on Santa Maria, I still managed to see seven different species in my seven years there, the rarest of which were Lanner Eleonora’s and Barbary. The first two were one-offs, but immature Barbary Falcons occurred almost annually, with one bird overwintering. No photographic opportunities presented themselves until I saw one catch a Grant’s Starling and take it to a fence post to eat. The fence was in a field several hundred metres away, but there was a ridge behind the field and I realised I could get reasonably close unseen. The ground was deeply pitted by cattle hooves after winter rains and I risked spraining an ankle at each step. By the time I finally peeped over the ridge, there was a buzzard sitting on the post, having robbed the falcon of its meal!

When I moved to the Algarve in 2016 I soon found that Barbary Falcons were also regular visitors. At first only immatures appeared, often staying in the area for several weeks, but in 2020 a sub-adult was seen intermittently between late August and late October and I managed to get distant but confirmatory photographs of it. The adult below in October 2023 came rather closer.

I am puzzled why this species has not been identified by others in Iberia, since both immatures and adults are quite distinctive. Their wing shape is quite different from Peregrine’s and there is little streaking on the underparts. Juveniles often have black-barred rufous tails. Its hunting technique also differs from its congeners, usually circling high and diving almost vertically at exclusively avian prey, unlike e.g. Hobby and Eleonora’s.

Back on Santa Maria, Peregrines occurred occasionally and a brown, pale-crowned juvenile of the Nearctic race arrived in October 2012 and stayed until the following March. At first it tried to take bathing gulls from the quarry lake but, after a while, they just ignored it! I saw it quite regularly but didn’t see it catch anything or find remains of a kill. Clearly of the previously unrecognised form ineptus!

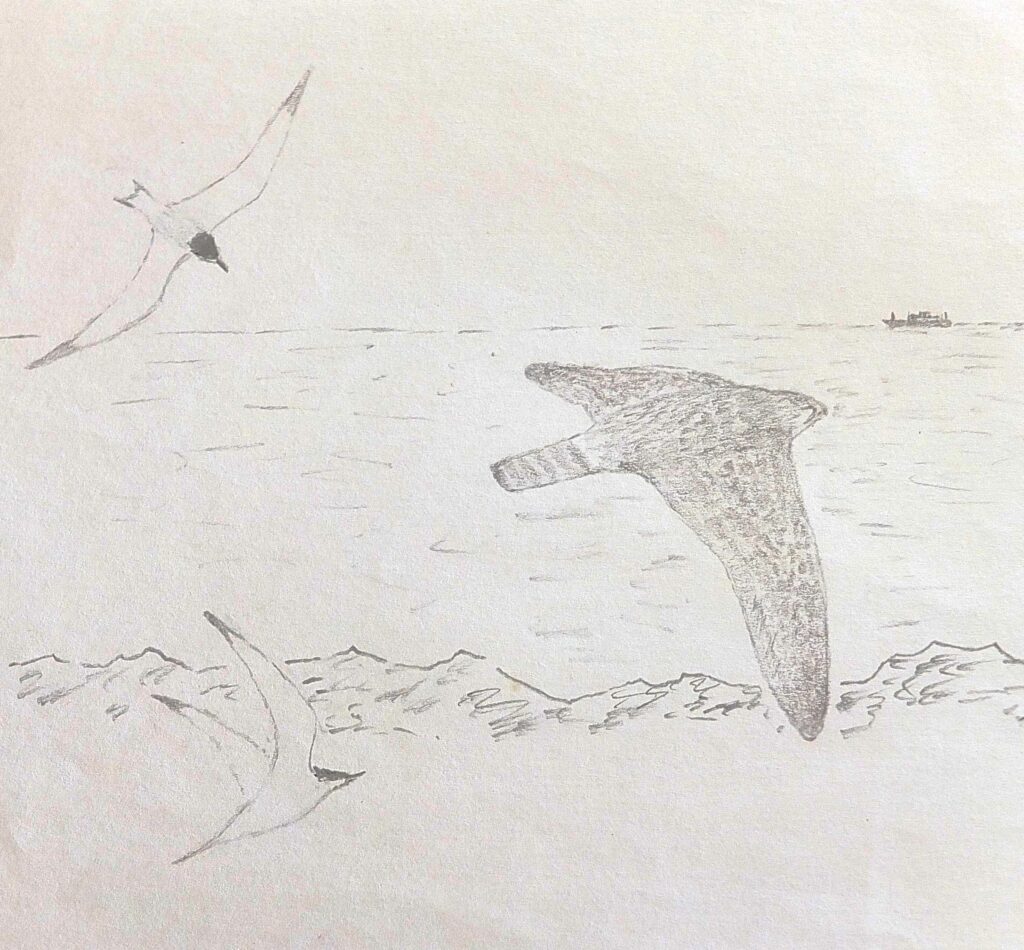

I wish I had been able to photograph the splendid white-phase Gyrfalcon which graced the Isles of Scilly for a few days from 8 May 1972. It was probably the bird which had wintered on the Sussex Downs. The grey-phase adult which passed over my garden on Santa Maria in early March 2010 was also too quick for the camera. In between these sightings, on 29 August 1992 I was seawatching at Brora when a pale grey/brown juvenile Gyr came in from just north of east (the normal arrival route from Scandinavia), was mobbed by Sandwich Terns and left to the south towards Tarbetness lighthouse. Young Gyrs become independent in about mid-August and the conditions were ideal for a southbound ‘overshooter’.

I sent the above sketch to Mike Rogers, explaining the supporting circumstances, but this interesting sighting met the same fate as most of my Sutherland rarities as well as the rock-solid, intermediate phase Eleonora’s Falcon I saw on Tresco in late September 1982. Mike preferred to accept the word of two inexperienced Cornish lads who had reported an ‘unusually dark Hobby’ on St. Mary’s that day, despite the fact that ‘dark Hobbys’ have never been reported before or since! Their mistake actually corroborated by sighting!